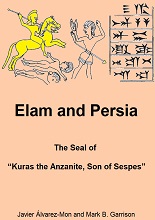

Among the thousands of administrative tablets and seal impressions discovered in the Persepolis Fortification archive, one artifact has consistently captured the imagination of historians and archaeologists: the seal designated as PFS 93*. Inscribed with the words “Kuras the Anzanite, son of Sespes”, the seal has become one of the most hotly debated documents for understanding the cultural and political world of southwestern Iran in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BCE. Unlike most seals of its time, PFS 93* bears not only images but also a personal inscription that appears to link it to the Teispid line of rulers—the ancestors of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire.

What makes this object so fascinating is the sheer weight of historical meaning it carries. It is not simply a carved cylinder rolled onto clay tablets; it is a symbol of dynastic memory, a bridge between the fading world of Elamite civilization, the rising power of Persia, and the looming presence of Assyria. Scholars have turned to PFS 93* to answer questions of chronology, genealogy, identity, and style. Was “Kuras the Anzanite” an early king of Persis? Was he related to the Cyrus mentioned in Assyrian annals? Or does the seal instead belong to a later generation, preserved as an heirloom by Achaemenid administrators?

This article introduces PFS 93* to the reader and provides a thorough analysis of its historical context, artistic composition, and interpretive significance. It aims to situate the seal within the broader cultural landscape of Elam, Persia, and Assyria, and to explore why this single object has become such a focal point in the study of early Persian history.

Historical Context: Elam, Persia, and Assyria

The story of PFS 93* begins in the turbulent centuries following the destruction of Susa by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 646 BCE. Elam, once a powerful kingdom with a long and distinguished history, entered a period of political fragmentation. In the wake of Elam’s decline, new regional powers rose in the highlands of Fars, particularly around the ancient city of Anshan (modern Tal-i Malyan).

It was here that the Teispid dynasty emerged. Teispes, known from classical and cuneiform sources, established himself as ruler of Anshan. His descendants, including Cyrus I and Cambyses I, extended their influence in the region. Eventually, this line produced Cyrus II, better known as Cyrus the Great, who in the mid-6th century BCE founded the Achaemenid Empire.

The title “Anzanite” or “king of Anshan” carried deep symbolic significance. It linked its bearer not only to the highland seat of power but also to an Elamite cultural heritage. At the same time, the kings of Anshan interacted with Assyria, sometimes submitting tribute, at other times asserting independence. Assyrian texts record that a “Kuras of Parsumas” sent a son to Ashurbanipal as a hostage following the sack of Susa. Could this be the same Kuras whose name is inscribed on PFS 93*? Scholars remain divided.

Thus, the seal must be placed against a backdrop of shifting identities: Elamite traditions merging with emerging Persian dynasties, local kings asserting legitimacy in the shadow of Assyria, and the formation of a political culture that would culminate in the empire of Darius and Xerxes.

Description of PFS 93*: Inscription and Imagery

The seal itself, preserved only as impressions on tablets, bears both an inscription and a carved scene. The inscription, written in Elamite, reads: “Kuras the Anzanite, son of Sespes (Teispes).” This is extraordinary. Very few seals from this period preserve the names of historical figures, and fewer still provide genealogical details. The mention of Teispes situates the artifact within the family line that later produced Cyrus the Great.

The imagery carved into the seal depicts a dynamic warfare scene. A horseman, armed with a spear, rides over defeated enemies. Below the horse’s hooves lie fallen figures, arranged in a stacked composition. Another figure flees, turning back in a gesture of surrender, offering up his broken bow. The scene is rich with narrative detail: conquest, submission, and the triumph of the mounted warrior.

When rolled onto clay, the seal produced impressions that were applied to Persepolis Fortification tablets dating to the reign of Darius I (509–493 BCE). Thus, the seal was already an antique when used in Persepolis, preserved across generations as a symbol of dynastic legitimacy.

Artistic and Stylistic Analysis

The style of PFS 93* has been at the center of scholarly debate. Early scholars such as Pierre Amiet classified it as an example of late Neo-Elamite glyptic art, associating it with seals from Susa dated to the late 7th and early 6th centuries BCE. He regarded its carving as uneven—an artifact produced by craftsmen of limited skill. Later analyses, however, have challenged this view, emphasizing the seal’s virtuosic execution.

The horse is carved with a powerful chest and finely detailed mane. The rider’s face, hair, and weaponry are carefully modeled. The fleeing figure displays expressive gestures of fear and supplication. Perhaps most striking is the spatial arrangement: the horse strides across fallen bodies stacked below, creating a sense of depth and layered meaning unusual in glyptic art of the period.

Comparisons with Assyrian palace reliefs are inevitable. Scenes of Assurbanipal hunting lions or battling Elamites at Til-Tuba show similar spatial conventions: victors riding above defeated foes, enemies turning in surrender, bodies layered in space. The broken bow offered by the fleeing enemy in PFS 93* echoes motifs from Nineveh, where defeated Elamites surrender their weapons in desperation.

At the same time, PFS 93* bears distinctive local features. Its Elamite inscription grounds it in southwestern Iran, and its stylistic vigor suggests a fusion of Assyrian influence with emerging Persian artistic traditions. It may represent the birth of a new style, generated in the upland environment of Anshan rather than the lowlands of Susa.

Symbolism and Identity

What does it mean to be an “Anzanite”? For the rulers of the Teispid line, this title asserted continuity with Elamite traditions while marking a distinct political identity. Anshan was both part of the Elamite cultural sphere and the cradle of Persian power. To call oneself “Kuras the Anzanite” was to root one’s authority in a highland identity distinct from both Assyria and the lowland Elamite centers.

The imagery of PFS 93* reinforces this claim. The victorious horseman embodies martial strength, while the defeated enemy dramatizes the submission of rivals. By inscribing his name and lineage, Kuras not only secured his personal memory but also created a dynastic emblem. When the seal was reused in Persepolis a century later, it testified to the enduring prestige of the Teispid line.

The heirloom character of the seal is also significant. In Achaemenid administration, antique seals carried weight as symbols of tradition and legitimacy. By reusing the seal of Kuras, officials in Persepolis invoked ancestral authority, connecting Darius’s regime to earlier kings of Anshan.

Connections to Assyria

The parallels between PFS 93* and Assyrian art are undeniable. Assyrian reliefs often depict enemies trampled under horses, weapons scattered across the battlefield, and gestures of surrender. The seal seems to borrow not only themes but also compositional techniques from Assyrian models.

Yet the adoption of Assyrian motifs did not imply submission. Instead, it may represent a local appropriation of imperial imagery to assert legitimacy. By adopting the visual language of Assyrian conquest, Kuras projected himself as a ruler of similar stature. The seal thus exemplifies a process of cultural borrowing and adaptation, where local elites reinterpreted foreign motifs to craft their own political identities.

The Seal in the Persepolis Archive

The discovery of PFS 93* in the Persepolis Fortification archive adds another layer of meaning. The archive, dating to the reign of Darius I, records the distribution of food rations to workers, travelers, animals, and deities. Seals were impressed on tablets as marks of authorization, often by officials or offices rather than individuals.

PFS 93* was not used as a personal seal but as an office seal, connected to the provisioning of the king. Its presence in Persepolis demonstrates the reuse of antique seals in Achaemenid administration. Far from being discarded, such seals were preserved and redeployed, carrying with them the aura of dynastic continuity.

Interpretations and Scholarly Debates

The key debates surrounding PFS 93* revolve around three questions:

-

Who was Kuras the Anzanite?

Some scholars identify him with Cyrus I, son of Teispes, known from Assyrian annals. Others caution that the evidence is inconclusive. The title “Anzanite” complicates matters, as it may refer to different regions or identities in different periods. -

When was the seal carved?

Stylistic analysis suggests a date in the late 7th or early 6th century BCE, perhaps during or just after Assyrian domination. Others argue for a later date, closer to the mid-6th century. -

What does the seal represent?

Is it a product of Susa, reflecting late Neo-Elamite traditions, or of Anshan, representing a new Persian identity? Was it carved by displaced Elamite artists working for highland rulers? Or does it embody a hybrid style born from intercultural exchange?

These debates remain unresolved, but they highlight the complexity of interpreting a single artifact. The seal resists simple categorization; it is at once Elamite, Persian, and Assyrian, local and imperial, antique and heirloom.

The Legacy of PFS 93*

The seal of Kuras the Anzanite, son of Teispes, is far more than a carved cylinder. It is a document of cultural transformation. In its inscription, we glimpse the genealogical roots of the Achaemenid dynasty. In its imagery, we see the interplay of conquest, submission, and royal authority. In its style, we detect the fusion of Assyrian models with local creativity. In its reuse at Persepolis, we witness the enduring power of dynastic memory.

PFS 93* thus stands at the crossroads of history. It marks the twilight of Elam, the rise of Persia, and the shadow of Assyria. It embodies the ways in which artifacts could carry identity, legitimacy, and cultural memory across generations.

For scholars, the seal remains a source of debate and fascination. For us, it offers a tangible connection to the world in which Cyrus the Great’s ancestors forged their authority. It is a small object, but one that contains within it the seeds of an empire.

Download the PDF Book Elam and Persia: The Seal of Kuras the Anzanite, Son of Sespes (PFS 93)

برای دانلود این کتاب، ابتدا باید عضو سایت بشوید.

پس از عضویت، لینک دانلود این کتاب و همهی کتابهای سایت برای شما فعال میشوند.

(قبلا عضو شدهاید؟ وارد شوید)